So, I begin my residency from just down the road in Nottingham. The pandemic has left me unable to visit Derby – which is obviously an interesting challenge for a site-specific project. So, I have no choice than to leap-frog into the city through all available portals. I’m resigned to the clunky websites of local history enthusiasts, maps provided by the all-seeing eye of Google and good old fashioned human conversation – albeit through the Zoomiverse.

Since the dawn of land ownership in Britain, common land has been a contentious topic. This last year public land and property has been a huge part of the post-pandemic zeitgeist – which comes as no surprise. Who gets to use certain spaces? What can and can’t you do in them?

I applied for this opportunity with the word ‘Psychogeography’ plastered all over my application. So, in order for you to follow my train of thought – I’ll start there.

What is psychogeography? This is the clear part, simply put it’s the way a place can influence one’s psyche. It does what it says on the etymological tin. Psychogeography was originally developed in the early 1950s. A gang of pan-European mavericks who would later be known as ‘The Situationists’ conjured up the field. With a penchant for red wine drinking and Marxist thinking, these flaneurs produced a number of books, exercises and visual art forms used to highlight the role of the built environment in our minds.

As with the situationists and Marxist thinkers of their time, modern ‘psychogeographers’ are greatly concerned with democratic and collective modes of existence, whether that’s through play, politics or place. Psychogeographer and prominent author Will Self argues that the urban environment is often one measured by two metrics – time and money. Our chosen route isn’t chosen at all. In fact, they are pre-determined.

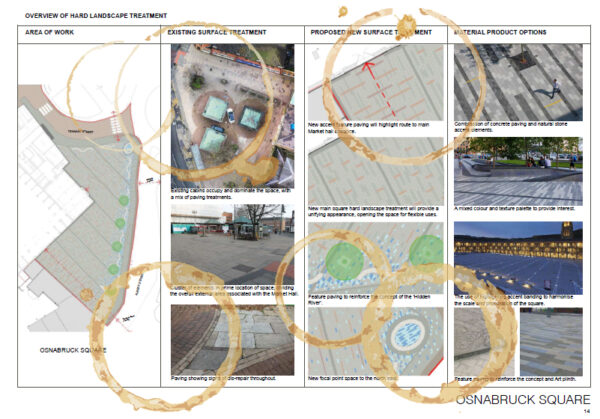

Take for example that new sculpture trail you’ve seen pop up in town – or the recently refurbished public square with it’s anti-septic stone flooring. It’d be a shame if someone spilt coffee all over it, which is likely – considering there are now five more coffee chains operating from the recently sold municipal building. These renovations and happenings might seem like philanthropic gestures for the public, but often they act as masks for the real incentive – to spend that sweet sweet nectar of consumer culture, cash monies.

Okay okay fine – I realise how gloomy I’m sounding. I doubt much of this information comes as a surprise. My goal here isn’t to tear down capitalism one aimless stroll at a time – nor is it to indoctrinate you into Marxism. I’m simply here to explore alternatives.

How do we generate new methods of navigation?

How do we encourage play and discovery without the expectation of financial contribution?

Over the next few months, I hope to explore collaborative ways of making and navigating, using the public commons of Derby – particularly Osnabruck Square – as my base. Maybe one day I can actually visit.

Architectural Plans for Osnabruck Square

Leave a comment