What silence brings

'What Silence Brings' is a large scale brush and ink drawing on silk, portraying a dark dystopian landscape which serves as a warning against today's social political and environmental climate. In the forefront is a huge tortured and dying tree, bound in wires and segregated from the rest of the picture by a gigantic grotesque wall, an obvious symbol of humanities detachment from nature. The landscape is dominated by a huge triangular crowd of people, who seem to be existing in their own worlds even within a crowd, looking lost and lonely, narcissistically amusing themselves to death, and entertained by their own Armageddon through the screens in their hands, seemingly unaware of the environmental catastrophe which surrounds them and how it will effect them. This apocalyptic nightmare dramatically depicts a precise moment in time, a massive flash of light illuminating the landscape coming from a mushroom cloud above, sending shock waves through the image and blowing branches from the tree. The melting of the ice caps, huge blocks of ice crumble into the sea and create cataclysmic waves heading for the land, the land which is now doomed behind the walls which they cannot even see behind the mass of plastic waste piled up. Leaning high up is a white flag, representing nationalism or perhaps a submissive cry for help. Barricades are warped into abstract shapes, which represent ideas of borders and barriers being just that, ideas and human-made

'What Silence Brings' is a large scale brush and ink drawing on silk, portraying a dark dystopian landscape which serves as a warning against today's social political and environmental climate. In the forefront is a huge tortured and dying tree, bound in wires and segregated from the rest of the picture by a gigantic grotesque wall, an obvious symbol of humanities detachment from nature. The landscape is dominated by a huge triangular crowd of people, who seem to be existing in their own worlds even within a crowd, looking lost and lonely, narcissistically amusing themselves to death, and entertained by their own Armageddon through the screens in their hands, seemingly unaware of the environmental catastrophe which surrounds them and how it will effect them. This apocalyptic nightmare dramatically depicts a precise moment in time, a massive flash of light illuminating the landscape coming from a mushroom cloud above, sending shock waves through the image and blowing branches from the tree. The melting of the ice caps, huge blocks of ice crumble into the sea and create cataclysmic waves heading for the land, the land which is now doomed behind the walls which they cannot even see behind the mass of plastic waste piled up. Leaning high up is a white flag, representing nationalism or perhaps a submissive cry for help. Barricades are warped into abstract shapes, which represent ideas of borders and barriers being just that, ideas and human-made

Categories:

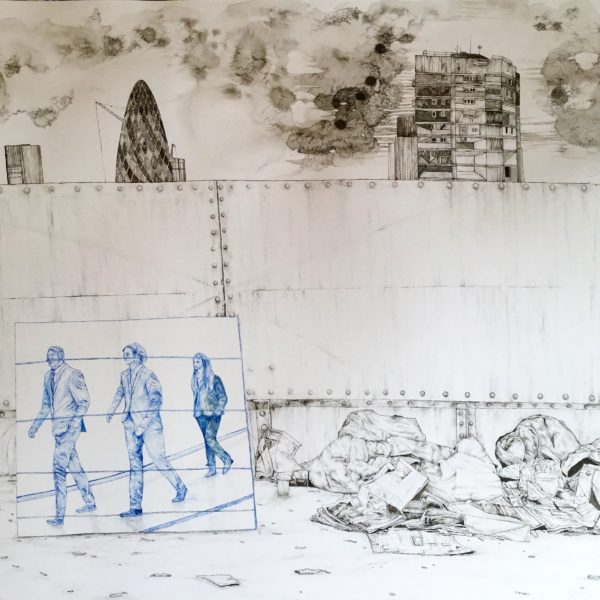

Gareth Bunting

Currently reading Timothy Morton’s 2013 publication, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, while making a series of works that somehow acknowledge, or attempt to acknowledge, the interrelationships between things; whether that be: lemons, capitalism, Jupiter, or Styrofoam. Hyperobjects – as outlined by Morton – ‘refer to things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans’ (p.1). They are also ‘directly responsible for what [Morton] call[s] the end of the world, rendering both denialism and apocalyptic environmentalism obsolete’ (p, 2). He notes: ‘A hyperobject could be the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, or the Florida Everglades. A hyperobject could be the sum total of all nuclear materials on Earth; or just the plutonium, or the uranium. A hyperobject could be the very long-lasting product of direct human manufacture, such as Styrofoam or plastic bags, or the sum of all the whirring machinery of capitalism. Hyperobjects, then, are “hyper” in relation to some other entity, whether they are directly manufactured by humans or not’ (p.1). I could continue here, but I think you get the point. Hyperobjects exceed human-scale temporalities; they are real regardless whether someone is thinking of them or not; you can’t point to them, or see them wholly (only in parts, at any given moment), and are unavoidably tied to the Anthropocene – the

Currently reading Timothy Morton’s 2013 publication, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, while making a series of works that somehow acknowledge, or attempt to acknowledge, the interrelationships between things; whether that be: lemons, capitalism, Jupiter, or Styrofoam. Hyperobjects – as outlined by Morton – ‘refer to things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans’ (p.1). They are also ‘directly responsible for what [Morton] call[s] the end of the world, rendering both denialism and apocalyptic environmentalism obsolete’ (p, 2). He notes: ‘A hyperobject could be the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, or the Florida Everglades. A hyperobject could be the sum total of all nuclear materials on Earth; or just the plutonium, or the uranium. A hyperobject could be the very long-lasting product of direct human manufacture, such as Styrofoam or plastic bags, or the sum of all the whirring machinery of capitalism. Hyperobjects, then, are “hyper” in relation to some other entity, whether they are directly manufactured by humans or not’ (p.1). I could continue here, but I think you get the point. Hyperobjects exceed human-scale temporalities; they are real regardless whether someone is thinking of them or not; you can’t point to them, or see them wholly (only in parts, at any given moment), and are unavoidably tied to the Anthropocene – the