Where are you based?

Manchester

How did your artwork start out?

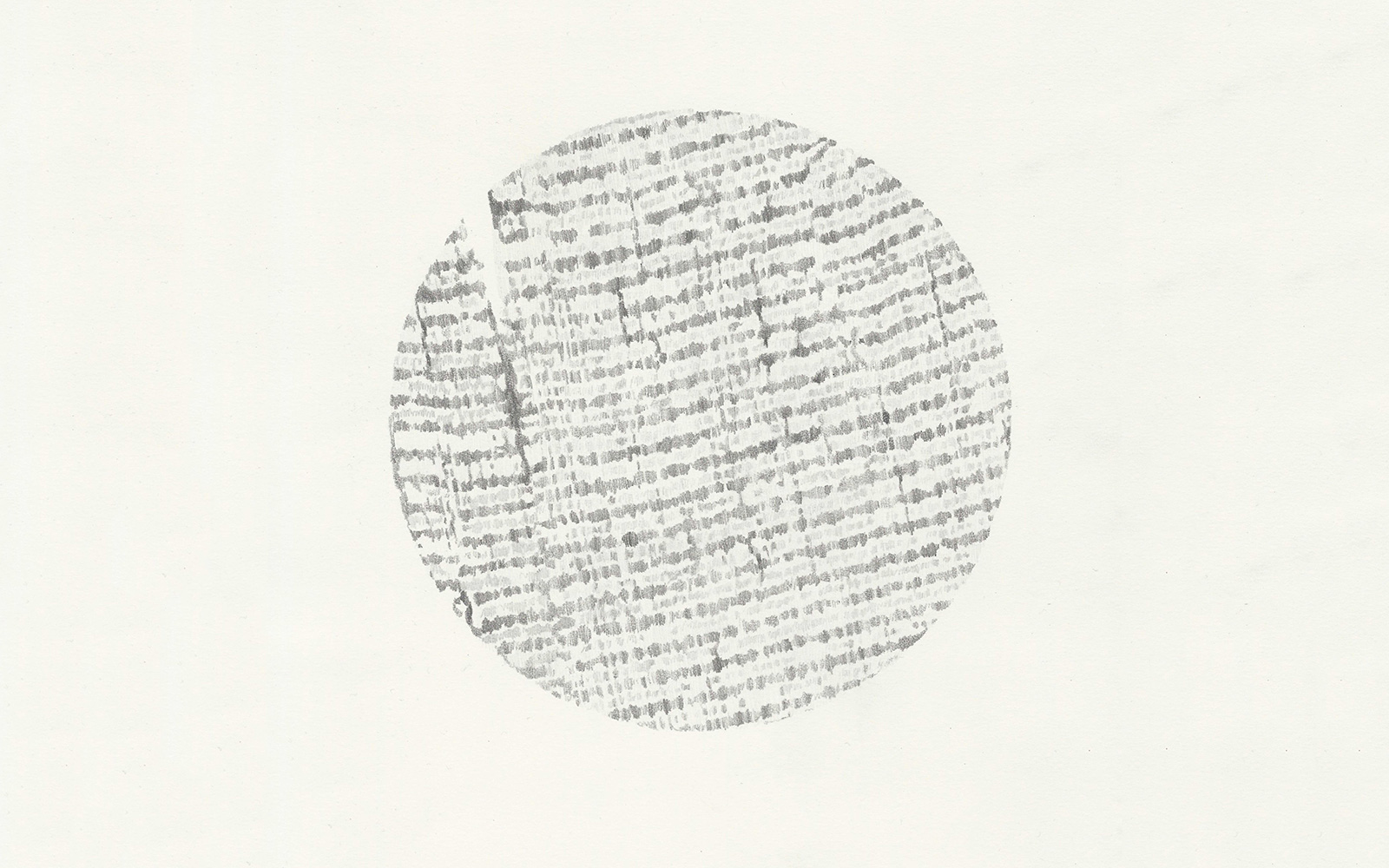

The human body has been an important theme in my practice from the very beginning. My undergraduate work focused upon skin: I used macro-photography to take highly magnified images of its surface, which resembled landscapes. I was also making direct imprints of skin using soft-ground etchings. Overtime, particularly after my MA, I became interested in how technologies look at, represent and measure the human body.

How do you get ideas for each piece of art?

My work is often research-led and responds to specific aspects of scientific enquiry such as data about air pollution, geographic mapping systems or medical imaging. I regularly undertake residencies in scientific institutions, and my conversations with scientists, as well as images from their research are often the starting point for ideas.

How do you go about transforming an idea like that into a physical piece?

Drawing is a primary method for thinking through ideas and of realizing them. It is a very direct and immediate way to explore ideas. I use methods and processes that respond in some way to my subject matter. For instance, I have used clay – a material that is unstable and slowly drops off the paper surface as it dries – to draw landscapes that are undergoing desertification. Or animal fat to draw the human brain, which is largely composed of fat.

How has your art evolved over the years?

My understanding of different scientific systems and processes has deepened through numerous residencies and projects with radiology units, geographical mapping systems, neuroscience, dermatology and Parkinson’s disease research. I recently completed an AHRC funded practice-led PhD, which investigated the concept of ‘noise’ in medical imaging. These experiences have fed into my artwork by opening up new methods and processes such as drawing from live bio-data whilst wearing bio-sensors. Over time, the scope of my practice has become wider and recent projects include installations, animation, performance and ceramics. However drawing remains at its heart.

What does your art aim to say to your audience?

I don’t make artwork to ‘educate’ or ‘illustrate’ scientific knowlede, but instead to allude to questions that remain unanswered, or to the persistence of the unknown (the noise) in science and technology despite huge and continuing advances in knowledge. I’m interested in placing science with social contexts.

What is the most challenging about your work?

When I am in scientific institutions, I am always outside my comfort zone. Artists and scientists use different terminologies, they understand knowledge very differently. For many artists, embodied and intuitive knowledge – often accessed through a direct engagement with materials in a sensory way – is highly valued and often used as a resource in their work. In general, scientists understand knowledge as factual, abstract and immaterial, it is often numerical and evidence based. Moving between these two positions is challenging.

Where did you get your ideas from? (see also above)

Residencies, conversations, the internet, the world around me.

Looking back at these works, what you do think about them now?

It usually takes me a long time to understand a piece of work, I find it quite difficult to ‘see’ work I’ve made very recently. I’ll need another year to tell you!

How and when have you decided to investigate themes that explore scientific processes of measuring, mapping and visualising the human body and its interaction with the environment?

I think I have already answered this question above so maybe we can delete this question?

What is the most interesting or inspiring thing you have seen or been to recently, and why?

A film I saw recently has haunted me for some time: Peter Jackson’s ‘They shall not grow old’. It is a reworking of archival footage from the Imperial War museum, which introduces sound and colour to original footage from the First World War and painstakingly equalises their varied film speeds. Whilst colorisation of old black/white footage is controversial and can be clumsy or overstated, here Jackson transforms the original footage into something extraordinary. He uses highly sophisticated twenty-first century technologies to create something even more tangible, immediate, sensory and ultimately more human. In my own work, I’m interested in the relationship between technology and human sensory experience.

Which other artists’ work do you admire, and why?

The drawings of: Nasreen Mohamedi, Agnes Martin, Rebecca Salter, Alison Turnbull, Julie Mehretu, Shahzia Sikader to name a few. Interestingly they are all women. I admire drawings that are slow – they take time in their making and demand time in looking, drawings that are highly sensitive to their materials, are contemplative and yet also unsettling in some way, that make you wonder and take you to somewhere unknown, and lastly that very very unfashionable thing – beautiful.

How do you see Kaipo Che! Residency, as an experience, to support your career?

The residency could have a very big impact upon my own identity as an artist. My proposal involves making collaborative drawings with India-based artists – a conversation with each other through mark-making. This seemed to me to be the perfect way to facilitate dialogue during my time in the Vadodara studios. Through this process, I will inevitably be exploring my own identity as an artist of Indian heritage who is also a first generation immigrant to UK.

What’s next for you in the future?

I will be returning to Dundee University to continue working with Dr. Miratul Muqit, who is researching Parkinson’s disease. The first phase of the project (September 2018) was a residency in the laboratories. During 2019, I will be making 3-4 further visits to spend time in the DCA print studio making new work in response to the residency, delivering workshops with patients and showing new work during a performative and interactive event in Dundee. I also have an upcoming solo show in February 2019 at PAPER gallery, Manchester.

Leave a comment